Funerals Are Big Pan-Africa, and Here’s Why Insuring it is Big Biz Too

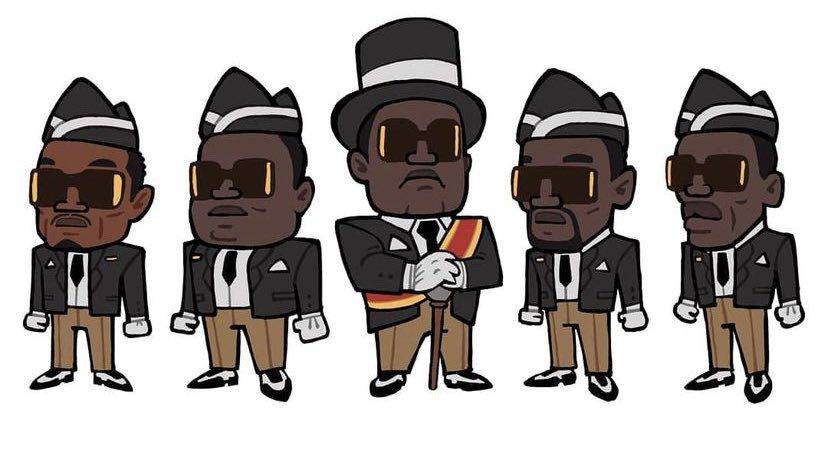

When BBC did a feature film on the Ghanian dancing pallbearers from the coastal town of Prampram in 2017, they had no idea it would take the world by storm. The group, referred to as Nana Otafrija Pallbearing, has its own set of internet memes, plastic dolls (made by an ambitious Hong Kong company for the souvenir market) and even former US President Donald Trump retweeting a morphed version of their original video. Today, this group led by Benjamin Aidoo performs internationally and for domestic markets — and continues to draw attention. In Latin America, Brazil, Peru and Columbian police used an edited version of the video to exhort people to stay at home and observe Coronavirus lockdown norms.

But it’s not just Ghana, which is big on celebrating funerals and the passing of life. Tina Maburu, a real estate consultant, from Ghana, says, “I have worked in SA, Tanzania and Ghana – and I have seen that across cities and tribes there is a general feeling that funerals need to be grand as its a way of honouring our elders.”

“It might seem funny. But, I remember attending a funeral in Tanzania with 1,000 plus guests. So the family had only informed 200 relatives, friends and colleagues. But each person invited took it upon themselves to bring their kids, parents and even distant aunts. While the funeral ceremony itself was not extravagant – the number of guests made the catering prohibitively expensive. And I felt amused that at many funerals, caterers and the family on auto-default ensured there was food for 800 – 1,000 guests. And these aren’t even rich people, but people from middle-class backgrounds.”

“And please don’t imagine gold-scroll coffins, a fancy music band, massive amounts of flower wreaths. That happens only with African politicians. For the middle class – a funeral gets expensive because of ceremony charges (how much you pay the pastor), catering and burial plot charges,” says Tina.

In Zimbabwe, there is a vibrant industry with burial plots for funerals. “I realised this when I was working on a construction project for a funeral company. They had made so much – just by promising nicer plots – shady, surrounded by trees, flowers,” says David Arumainayagam, CEO, real estate development firm Urban Rises in Zimbabwe. In fact, in the central business district of Harare – you will find insurance company offices jostling for space with undertakers and coffin manufacturers — resulting in it being dubbed as “Death Valley.”

In Kenya to cope with the high cost of funerals, many people make public appeals. What in earlier days used to appear in the form of posters on city walls have now transitioned into social media posts. For instance, Debora Nabubwaya used “GoFundMe” for contributions towards her aunt who died in Eldoret, Kenya from breast cancer. And with cultural assimilation, even expats in Kenya – go with cultural pressure and norms for a fairly elaborate funeral. For instance, fellow activists and friends of British expat activist Joan Smith made a social media appeal to cover her medical and funeral expenses.

Kenyans say – most middle-class households are just one medical emergency away from bankruptcy. “When my uncle died, his wife was making a 6 figure salary and yet we were all scrambling to help with transport and funeral costs,” says Jane Ndongmo.

And transport costs could be steep, says Saruni Maina, Founding Editor, Gadgets Africa. “It is customary to be buried in your home village and that could mean a journey of anywhere from 400-750 km from Nairobi.”

So where does insurance come in?

Africa’s insurance industry is worth USD 68 Bn and is the eighth largest in the world, according to a report by McKinsey. Though this isn’t evenly distributed. South Africa, the largest and most established insurance market, accounts for 70% of total premiums; followed by Morocco, Kenya, Nigeria, Egypt, Zimbabwe, others.

But oddly, funeral insurance forms a huge chunk of life insurance. “In Zimbabwe, funeral insurance sales comprise 68% of the total life insurance market,” says Mustafa Sachak, CEO, Zimnat.

And these are family floater covers. “It covers one’s parents, in-laws, spouse and kids. We offer a maximum cover of ZWD 1 Mn (USD 2,763) for a family consisting of spouse, 4 kids and their parents. And the premium will be roughly about ZWD 6,300 (USD 17) if the elders in the family are below 75 years of age. But this is at the high-end,” says Sachak. “At the lower end, our minimum cover is ZWD 100,000 (USD 276) with a premium of ZWD 1,260 (USD 3.5).

And these plans take into account the probability that it’s more likely — that the breadwinner is paying for his parents or in-laws funerals. “For the funeral covers, in case of the death of a parent one has access to 50% of the main cover. That means in the 1 million cover, parents are covered up to ZWD 500,000 (USD 1,381).

In Kenya, the Association of Kenya Insurers say, the most popular plans are those that cost between KSH 1,200-3,000 (USD 10-23) for coverage of KSH 100,000- 300,000 (USD 921-2,763). In Kenya, insurance sales is primarily driven by insurance agents – but in recent years bancassurance and online platforms have also become key distribution channels. For instance, Edith Chumba – head of retail banking Kenya & East Africa, Standard Chartered, while launching “Farewell Plan” in partnership with Sanlam Insurance underpinned that “funeral costs tend to be very expensive in our society.” The Farewell Plan offers up to 1 million cover — i.e. KSH 1 Mn (USD 9,212) — signalling the rise of the upwardly mobile salaried class in Kenya.

Low-income or Upper-middle class product?

In 2010, when ILO Microinsurance Innovation Facility did a survey of microinsurance practitioners in Africa it found that 14.7 million people in 32 African countries were covered by microinsurance products. More than half (8.2 million) were in South Africa, where funeral insurance was by far the biggest microinsurance product. The survey also revealed that of life insurance taken by 9.1 million low-income households, 6.2 million had funeral cover.

Life insurance premium as a percentage of GDP was 9.4% in 2010 in South Africa. Fast forward to 2019, and life insurance as a percentage of GDP was 13.75%, as per data with Swiss Re. Funeral covers as a part of life insurance have also grown — from being a microinsurance product targeting low-income households it has become a middle-class and upper-middle class product with biggies like Discovery, Liberty, Momentum, Old Mutual and Sanlam Insurance offering the same.

“What has really marked the paradigm shift is large corporates now buying funeral insurance for their employees. And getting such group cover business is far more lucrative a proposition for insurers than individual insurance sales. When you look at the cost of customer acquisition – getting one individual to sign the dotted line takes quite a bit of convincing from our insurance agents. But when it comes to corporate group covers – it’s just one cover but funeral insurance for anywhere from 500 – 2,000 employees,” says an executive at Old Mutual.

Covid-impact

The country’s top five insurers lost ZAR 8 Bn (USD 540 Mn) of value, compared with ZAR 32 Bn (USD 2.1 Bn), as per PwC data. The combined group embedded value of insurers fell 9% both due to higher claims during covid and lower investment income from turbulent markets. Insurers say, the higher claims experience in SA was due to more Covid-19 deaths and non-Covid deaths as the healthcare system got clogged with the pandemic.

As per data with ASISA (Association for Savings and Investment South Africa), total claims paid in 2020 rose 6% year-over-year to SAR 523 Bn (USD 35 Bn) in 2020. While this spelt bad news for the industry — as SA’s top five insurers posted a loss of SAR 870 Mn (USD 58 Mn) in 2020 compared to a profit of SAR 22 Bn (USD 1.5 Bn) in 2019; insurers say long-term this will reap dividends.

“Yes, 2020 was a bad year for two reasons. One, insurers paid out heavier in claims. Secondly – for an insurer investment income contributes a sizeable portion of revenue, and this year the economic downturn and market fluctuations met poor returns on investment. But long-term, this will prove positive as the pandemic has made policyholders more aware about the need for insurance,” says an executive at KenIndia Assurance.

Insurers say post-pandemic they have seen an increase in sales from fresh-to-insurance customers. While its still early days for 2021 data to show a growth in sales, insurers say internal numbers and anecdotal evidence point to the fact that Africans have increased awareness on the need for both life and funeral insurance. Another marked trend is old customers are now upgrading existing policies for higher coverage or buying additional covers. “Cross-selling has gained importance. Customers who have bought funeral covers, have allowed themselves to be persuaded into buying life insurance and pension plans,” says Sachak.

Image credit: Benjamin Aidoo, Twitter